|

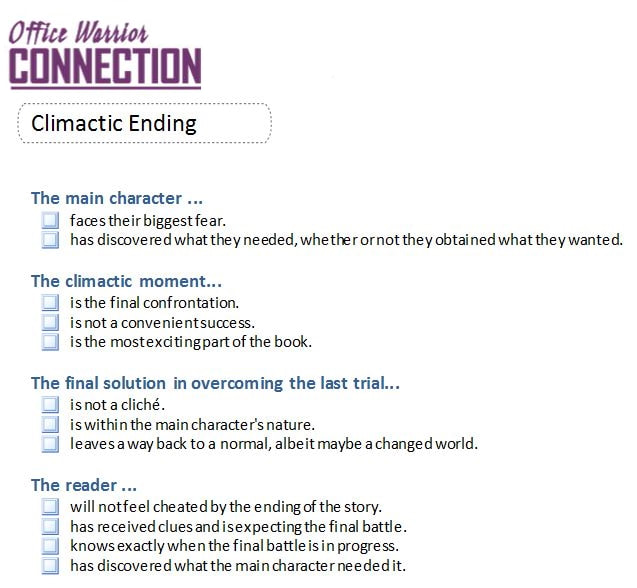

5/25/2019 Day 25 - Climactic EndingWhat are the elements of a great climactic ending? A great climactic ending won't just be good winning over evil in a final heroic battle. A battle without an emotional element is just a battle. And a battle that doesn't stand out among many battles in a great war replete with battles is just another battle. The final battle should be the most important, most revealing scene in a novel. A climactic ending will have a whole series of events that lead the reader right up to the battle. It will be the highest point of tension in the story, the moment the main character has to do or die, and if the writer wants the reader to really love the book, the final solution cannot be a cliché or be out of the main character's wheelhouse. The writer will need to provide all the clues necessary throughout the rising action that the reader is not surprised by anything the main character does to win. For instance, if the main character has never been a cheater, cheating to win would not only be unexpected by the reader, but also out of character for the main character. It is often during these last chapters when the reader discovers what the main character has needed all along. They may have started out on the journey wanting to take down an evil empire, but discover that they had a deeply buried need to discover the father who was never around when they were a child. Sound familiar? Exercise: Climactic Ending Checklist

Many of the items in the Climactic Ending checklist will have already been tackled by previous exercises, so this is an opportunity to review and make sure you haven't missed anything.

Climactic Ending Checklist The main character ...

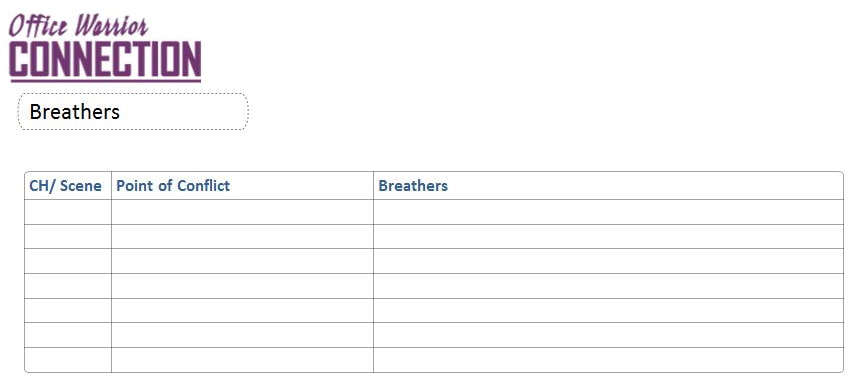

DOWNLOAD: Climactic Ending Worksheet Template Instructions Return to the Table of Contents Go to Day 26 - Dialog Tags What is a lagging middle? A lagging middle is what sometime occurs after a main character has set out on their journey to find love, solve a mystery, or overcome the villain, but they haven't yet reached the final confrontation. If the story meanders along without an apparent goal in sight, or the trials become too repetitious without having an emotional effect on the main character, the writer risks the reader becoming disengaged from the story. Needless to say, stories need to move forward, gather momentum, and launch readers into the climax with fear in their hearts for the heroes. How do you tell if you have a lagging middle? Unfortunately there is no perfect method for discovering whether or our own stories have low points other than making sure you have a strong story structure. On Day 9 you mapped our story to the classic story arc and that should have revealed places where the story needed work to bring it in line with reader expectations. The best way to tell if you have a lagging middle is for someone to tell you that you do. This means you might not find out you have a lagging middle until you have someone read your story and provide in-depth feedback. At some point, you may be ready to have beta readers take your story for a spin. Listen closely to what they tell you. If they tell you they were bored at any point in the story, that is an opportunity to fix the lag. How do you fix a lagging middle? You've already looked at several ways to fix a lagging middle. On Day 11 you looked at making every scene in your story purposeful. This means you've already examined your scenes to confirm your story is moving forward. If you completed the Character Arc exercise from Day 15, you've also confirmed that your readers will care about your characters. You've even tested your momentum in the exercises covering Pacing from Day 12 and Tension from Day 13. The only other thing you can do at this point is focus on the breathers. What are breathers? Breathers are the space between tension in a novel. They are the physical or mental break we give our character as they transition from one challenge to the next as they make their way to achieving that thing they wanted in the beginning of a story. Breathers can be fast or slow, high or low. Depending on where you are within the story, your breather should be used as a method of setting the pace of the story but also of giving the reader "down" time after an emotionally charged scene. If you think of a highly dramatic movie, we are kept on the edge of our seats by the low build-up of oncoming drama as we are by the highly charged moments of an internal or external battle. This exercise is one more opportunity to focus in a bit tighter on pace to make sure you don't have a lagging middle, so focus on the middle 50% of you story. Yes, this is very subjective and yes you may have done this perfectly while writing without even thinking about it. Keep in mind this is just one more tool that you can use to perfect something that may already be very good or fix something that you initially thought was "just fine as it is." Exercise: Review Breathers

Analysis of Breathers Does the breather have an obvious purpose?

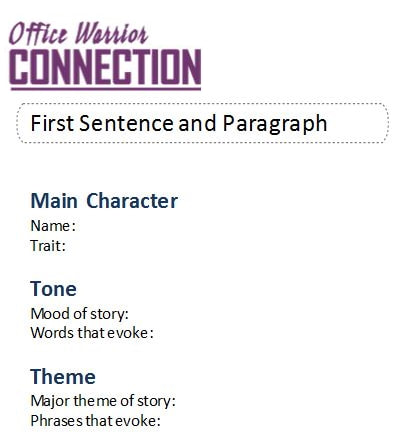

DOWNLOAD: Breathers Worksheet Template Instructions Return to the Table of Contents Go to Day 25 - Climactic Ending 5/23/2019 Day 23 - First Sentence, First ParagraphThe First Sentence The first sentence of a story is an important but often overlooked element of a good book. A great first sentence will be remembered along with the characters and story itself. One of the most famous of first lines that I hear quoted by people is only a partial quote. "It was the best of times, it was the worst of times..." The rest of the quote from A Tale of Two Cities, by Dickins, seems to be lost in the number of words required to memorize the full quote. The other famous line I sometimes hear quoted is from a book that I would be surprised to discover the people quoting had ever read. "Call me Ishmael" is from Melville's classic, Moby Dick. My personal favorite is from a treasured childhood book by S.E. Hinton, The Outsiders. "When I stepped out into the bright sunlight, from the darkness of the movie house, I had only two things on my mind: Paul Newman, and a ride home." I'm not sure what struck me about that line, or whether it was because it both began and ended the story, but at the young age of twelve, I was hooked. The first sentence should name or at least reference the main character. If the story is in first person, "I" should be addressed. The second thing the first sentence should do is set the hook. It should be a powerful sentence that makes the reader ask a whole lot of questions. Why is the narrator saying to call him Ishmael? Is that not his real name? Why is a ride home on Ponyboy's mind? How did he get to the movie house? Why was he watching a movie in the middle of the day? The First Paragraph (or two) The first paragraph of The Outsiders goes on to make a comparison between the first person main character, Ponyboy and Paul Newman. It sets the stage by introducing us to a teen boy with usual teen boy angst and hints at the major theme of the story: the differences between the haves and the have-nots. I was hooked. Even though I was a teen girl, I was hooked hard by this boy wishing he looked like someone else but also not wanting to change because he knew he fit in where he was and would have to give up his beloved family and friends if he did change. Hooked. That is what the first line and first paragraph should do. They should hook the reader so hard that they stand in the bookstore with the book open in their hands unable to put it back on the shelf or even walk to the counter to pay for it. The first paragraph should start building a mood right away and add a bit of suspense and present the major theme in some way. One of the major themes in The Outsiders is rich vs poor and S.E. Hinton captures it perfectly right off the bat. Today's exercise includes a worksheet you can work on in order to confirm you have all (or at least most) of the elements that make up a good first sentence and first paragraph. If you're skeptical of the list, pull out your favorite novel and see how it's first sentence and paragraph or two stack up. Exercise: Confirm a Great Beginning

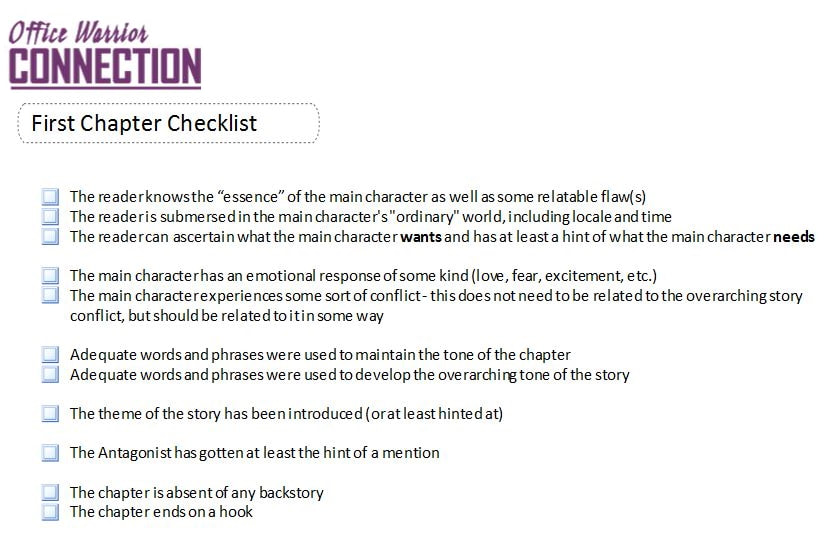

Exercise Parameters Main Character: Who is your main character and what is their most obvious attribute or life philosophy that has an effect on the story? Fill in the name and the trait. Tone: What is the mood of your story? It doesn't have to last throughout the whole chapter or the whole act, but will help the reader settle in on what's to come if you can strike the right tone straight out of the gate. Write down the mood you believe your story struck. The best way to set tone in a single paragraph is by word choice. Think about what is the mood of your story, then do some word association to come up with words that fit the mood. Add your words to the worksheet. Try coming up with some synonyms as well. Once you have a couple words in hand, see if you can work them into the first paragraph. Theme: What is the message you want to convey with your story? Like tone, very early on we want to evoke a sense of what the story will be teaching our readers by the time they finish. Write down the major theme of your story. It may be hard to capture a theme in a single word, so instead, think about phrases that reflect the theme. Once you've gotten a list, see if you can work a phrase or idea that represents your theme into the first paragraph (or two). DOWNLOAD: First Sentence and Paragraph Checklist Template Instructions Tips for working by hand If you'd like to work on notepaper or set up the headings and parameters in your favorite application, include those listed above. If you are going to work by hand, give each parameter space for notes even if you plan to work down from the top because you may find as you start thinking that other ideas come to mind as you work. Return to the Table of Contents Go to Day 24 - Better Breathers to Eliminate a Lagging Middle 5/22/2019 Day 22 - First ChapterThe Importance of an Engaging First Chapter The first chapter is just as important as the first sentence and first paragraph since the first chapter is what will help a reader decide to keep reading or try something else. Within the first couple of chapters, you will introduce the reader to your main character, reveal the setting, set the time frame, and show the reader what every day life is like for the main character (all stuff I talked about in Day 9 when we mapped our chapter summary to a story arc). The first chapter won't engulf all those elements, but it should have some features that engage the reader and keep them reading. Today's exercise includes a checklist you can work from in order to confirm you have all (or at least most) of the elements that make up a good first chapter. If you're skeptical of the list, pull out your favorite novel and see how it's first chapter stacks up. Exercise: First Chapter Checklist

First Chapter Checklist

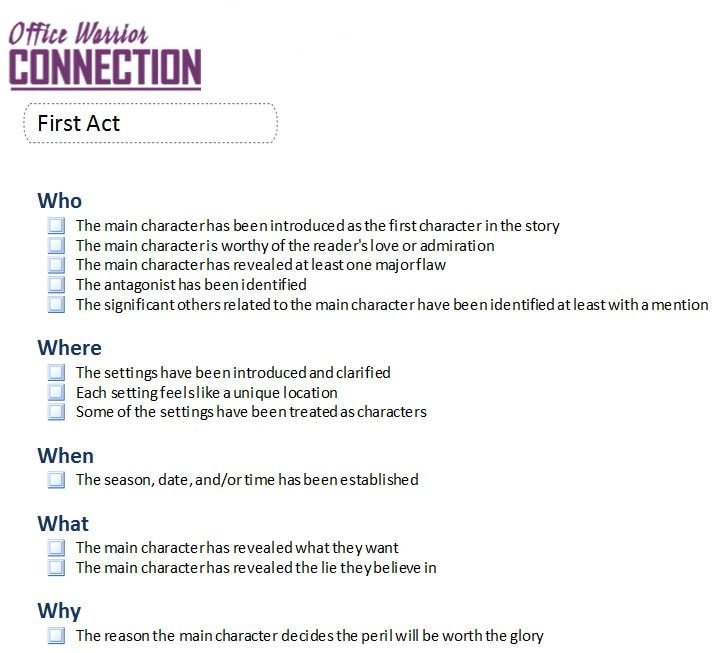

DOWNLOAD: First Chapter Checklist Template Instructions Return to the Table of Contents Go to Day 23 - First Sentence, First Paragraph 5/21/2019 Day 21 - First ActThe First Act The first act of a novel is the first 20-25% of the story. The first act is an introduction to the main character and the purpose of the story. It should encapsulate all the answers related to the 5 W's: Who, Where, When, What, and Why, and it should do all of that before any of the real action begins. The reader should learn what everyday life is like for the main character and what they want that they can't obtain because of some lie that they believe. After you confirm you have all the elements of a good first act, you will start narrowing in on the first chapter, then the first paragraph and first sentence. Each level has its own set of key elements. Today's exercise includes a checklist you can work from in order to confirm you have all (or at least most) of the elements that make up a good first act. If you're skeptical of the list, pull out your favorite novel and see how it's first act stacks up. Exercise: First Act Checklist

Many of the items in the First Act checklist will have already been tackled by previous exercises, so this is an opportunity to review and make sure you haven't missed anything.

First Act Elements List Who

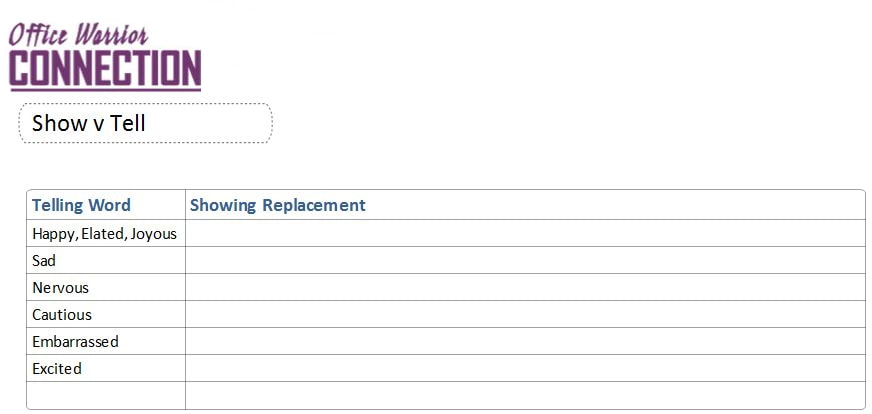

DOWNLOAD: First Act Checklist Worksheet Template Instructions Return to the Table of Contents Go to Day 22 - First Chapter 5/20/2019 Day 20 - Show or TellTo Show or To Tell, That is the Question There is a lot of discourse out there about whether or not you should show or tell when you write. Popular opinion seems to fall to the side of a preference for showing instead of telling in order to draw the reader into the story, but it is my opinion that there are appropriate times for each. Telling is when the words used in the moment tell us exactly what a character is feeling or what mood is supposed to be set. For example, the following sentence is "telling." She was embarrassed. Showing is when a description of an action or event allows the reader to decipher on their own a mood or feeling. For example, the following sentence is "showing." His cheeks flushed a crimson shade of red and his eyes would not meet mine. Rather than tell you that you should never use "telling" language or dialog and always using "showing" descriptions, I think it's better to consider when it's appropriate for each. I even believe there are instances where it is perfectly appropriate to use both in one paragraph. When to Show Methods of showing work well when you want to convey an emotional aspect of a character in a way the reader can relate or when you want to paint a more memorable picture of a character, scene, or action. It would be very appropriate to have a lot of showing moments in the beginning of the story when you are introducing a character and setting the ground work for the world(s) in which they operate. When to Tell Methods of telling work well when you are in an action sequence and do not want to interrupt the pace with flowery text or when a character has to take several steps that are non-consequential and you need move the plot forward. For instance, the reader does not need to know every step taken from the moment a character woke up, did their morning constitutional, and ate breakfast. Instead, jump right to, "After breakfast..." More telling will likely occur as you get closer and closer to the climactic moment of your story. In those moments when the action is gearing up and the pace of the story is becoming quicker, paragraphs and long sentences will pull the reader out of the action sequence where as a quick telling of what is going on will keep the activity in motion. In other words, I don't care what the debutante is wearing the moment she begins having an argument with person who brought her. Keep me engaged with the moment of stress. When to Show AND Tell High action sequences sometimes require both showing and telling in the same paragraph or scene. Consider a sword fight in a comedic scene. Telling might be used to set forth the thrusts, parries, and footwork to get us through the bulk of the scene, but the comedic moment when the soldier's belt is sliced apart and his pants to his great horror fall to his knees might be better served with a bit of showing. It would also be appropriate to use both showing and telling if you have a narrator who interrupts scenes. Again, this is sometimes used as a comedic style, but I've seen it used in other dramatic novels as well. For example, a dramatic action scene is just coming to life when the narrator cuts in to give a bit of backstory or a character pauses, looks out at the audience and speaks directly to them. If you have seen The Never Ending Story or The Princess Bride, you've seen this style of show and tell occurring. It's very effective, but it won't necessarily work if you haven't already presented the narrator or the character as someone who will be interrupting in that way unless you show they are like that during your initial introduction. Exercise: Create a Show v Tell Worksheet

Since the tendency is to tell when you should show, we will use this exercise to seek out and correct instances of telling, but be aware that you should also be cognizant of situations where you are showing but would be better served by telling.

Parameters Telling Words - List all the possible feeling words that you suspect you may have used in your manuscript. For example, some of the feelings your characters may go through might include: happy, sad, angry, nervous, cautious, embarrassed Next, add all the synonyms that you can think of (or check on webster.com or another site that lists synonyms). Showing Replacement - Write ways to show the emotion instead of telling. For instance, if you used the word "happy," what are the ways you could express happy with descriptions of body language? What does happy look like on someone's face? What does a person do with their hands or their feet when they are happy? If you need assistance with how to demonstrate different emotions, look at the cheat sheets on Writers Write(https://writerswrite.co.za/cheat-sheets-for-writing-body-language/) or Jeni Chappelle's helpful post 9 Simple and Powerful Ways to Write Body Language (http://www.jenichappelle.com/2014/09/body-language/). WritersHelpingWriters.com has also published a book called the Emotion Thesaurus worth considering if you need even more help with writing how people express emotions. Instructions

DOWNLOAD: Show v Tell Worksheet Template Instructions Return to the Table of Contents Go to Day 21 - First Act 5/19/2019 Day 19 Eliminate Info Dumps What's an Info Dump? An info dump is an over-explaining of information related to your story that takes the reader out of an active scene. It is "dumping" a lot of information all at once and leaving it to your reader to figure out how it relates to your story or the scene and why its important to your main character. New writers will sometimes do info dumps near the beginning of a story when they are providing backstory, explaining magic elements, scientific facts, or historical events when instead they should be introducing the reader to the main character in their current environment and situation. Is all info dumping bad? No. Very specific and intentional Info dumping can be used as a gimmick. The best example of this is when a narrator telling the story is a specific character and they “take a moment” from their story telling to explain a character’s motivation. Comedic writing can also use it to great effect as they ramp up for a punchline. Science fiction and fantasy writers will also spend more time world building than say a romance writer simply because they are creating a whole new place filled with different rules and elements than what we normally experience. The first quarter of the book Dune by Frank Herbert was painfully slow for me the first time I read it because it goes into painstakingly long descriptions of the spice planet. Some might criticize that, but without the information, the reader would be left wondering why people were behaving and reacting they way they did throughout the story. Even lighter works can use info dumping to great effect. Many teen mysteries and cozies info dump at the end of the story. If you have ever watched any episode of Scooby Doo, you'll have seen this. It's when Fred or Velma explain away the mystery. This sort of info dumping is perfectly accepted. And it's because it's at the end of the story. It's fun because they are walking us through how they used the clues they were given to solve the mystery. The clues are what is sprinkled through the beginning of the story, not the an info dump. We are faced with two questions when examining our own stories for info dumps. First, How do we spot the bad ones? And second, how do we fix them? How Do We Find Info Dumps? One of the easy ways to spot an info dump in your work is to look for long paragraphs. You can skim your chapters for very long paragraphs and then zoom in on them to see if you have dumped a chunk of information on the reader. Another way you can find your info dumps is to think about the places in your story where you know you added backstory or flashbacks, or spent time describing abilities (magical or otherwise), technology, rules of law, fantasy creatures/races, etc. Once you find a paragraph that you think might be questionable, here's what to ask yourself:

Exercise: Find and Fix Info Dumps Info dumping done poorly is often associated with lazy writing by "the people in the know" and boring by readers who don't see it for what it is but sense that it's there, so it's worth the time spent in fixing it. So, how do we do a sufficient bit of world building without dumping all the exposition all at once? "All at once" might give you the biggest clue. The goal should be to roll out large chunks of information in smaller bits throughout the story.

Methods for fixing Info Dumps

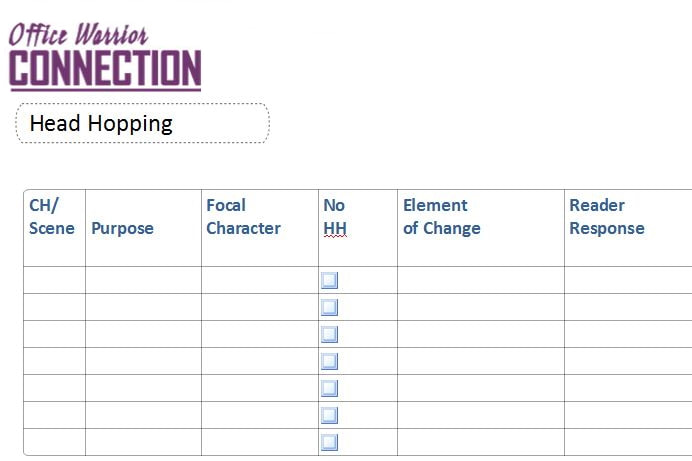

Return to the Table of Contents Go to Day 20 - Show or Tell 5/17/2019 Day 17 - Head HoppingWhat is Head Hopping? Head hopping is the unintentional change from one character point of view to another, exposing their inner thoughts or feelings, without any warning or proper break. Unless you are writing from a purely omniscient point of view wherein the omniscient being can jump into every character's mind, we should not be hearing voices from multiple characters in a single scene, or in the event you write short chapters, in a single chapter. Head hopping is disorienting. It pulls a reader out of the story to pause and figure out what just happened or who just thought what and sometimes even go back to reread to try to understand. It makes it harder to identify with a specific character and it is generally seen as inexperienced writing. If you need to switch perspectives, the best solution is to create a break that still allows good flow between the end of the section and the beginning of the next. This may be a chapter break or a scene break. Either way, the reader needs a definite clue that the perspective is changing between the characters. How Do You Spot Head Hopping? Some head hopping will leap right off the page at you. It can reveal itself by that sudden feeling you have of being lost about who said/thought what. Other times, the head hopping can be quite subtle and unless you are specifically head hopping hunting, you might miss it. Spotting head hopping requires an analysis of character thoughts and behaviors, one scene at a time. It means determining which character has the focus or point of view in each scene, then intentionally reading to confirm that point of view has not unintentionally shifted to another character. Here is an example: Clara walked to the kitchen while she tied her bonnet onto her head. She reminisced about the fireworks from the evening before. Daniel had gotten a bit more friendly under the stars than she had been prepared for, but if she were being honest with herself, she had found it exciting. She felt her cheeks grow warm with the memory of his hand resting on her knee just as she pushed the kitchen door open. Daniel stood in front of the stove flipping a pancake high into the air. "What on earth are you doing?" Clara asked. Daniel flinched and spun around. He knew she wasn't as happy as he thought she would be. The excerpt begins from Clara's perspective. We walk along with her to the kitchen and experience a bit of her inner thoughts about what must have been a bit of a racy evening for her. But suddenly, just when she confronts Daniel, we are suddenly in his head. When the writer tells us what Daniel knows, that is a jump right into his head. How Do You Fix Head Hopping? Fixing head hopping requires a bit of creativity. Often head hopping, like the example above, reveals itself in a moment of "telling" when instead it should be a moment of "showing." Rather than telling the reader what Daniel is thinking, the writer should continue to show us, just as was done in the sentence before the head hopping... "Daniel flinched." The question is whether that two-word sentence is enough for the reader to make the leap from flinching to knowing that meant Daniel knew Clara wasn't happy. In this case, I don’t think there is quite enough context. Show, don't tell. Instead of telling the reader that Daniel can see Clara isn't happy, use some description that is more in line with showing us his feelings. In the case of the sample text above, the last sentence might be revised to: Daniel flinched and spun around. His eyebrows drew together. More about show versus tell will be coming in a few days! Use dialog. It would probably be annoying or in the least, feel weird, if every secondary character were telling us how they were feeling every time they turned around. However, using dialog can be an effective way of getting to a character's inner turmoil. Instead of coming right out and saying, "I'm sad," however, consider other ways a character (while keeping in context of who that character is and what their personality is like) might say they're sad without stating it directly. In the case of the sample text above, the last sentence might be revised to: Daniel flinched and spun around. His eyebrows drew together. "I thought you would enjoy a pancake for breakfast." Delete. If you can remove the head hopping portion of the paragraph without it affecting the story or the scene, consider removing it. If you had a large portion of text and dialog that you believe could be removed, don't delete it! Move it to a back up location. Maybe it is part of a scene you can use in another story! Exercise: Modify the Purposeful Scenes Worksheet

For today's exercise, you can reuse the Purposeful Scenes worksheet competed on Day 11 [link]. If you didn't do that exercise, you can create the worksheet from Day 11 and just use the Scene, Purpose, and Focal Character columns.

Tips for working by hand If you are working by hand and still have your Purposeful Scenes worksheet, see if you have room in one of the margins to make your "No HH" notation. Another option would be to use a colored pen or a highlighter to cross items off as you check them. Return to the Table of Contents Go to Day 18 - Analyze Dialog |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed